In the first of a two-part series on planning for bluewater cruising, Vicky Ellis looks at how to be prepared for almost anything

So what makes a good bar story out of a bad situation? What problems and challenges are we likely to face on the picture-perfect voyage and what does it take to cope and succeed?

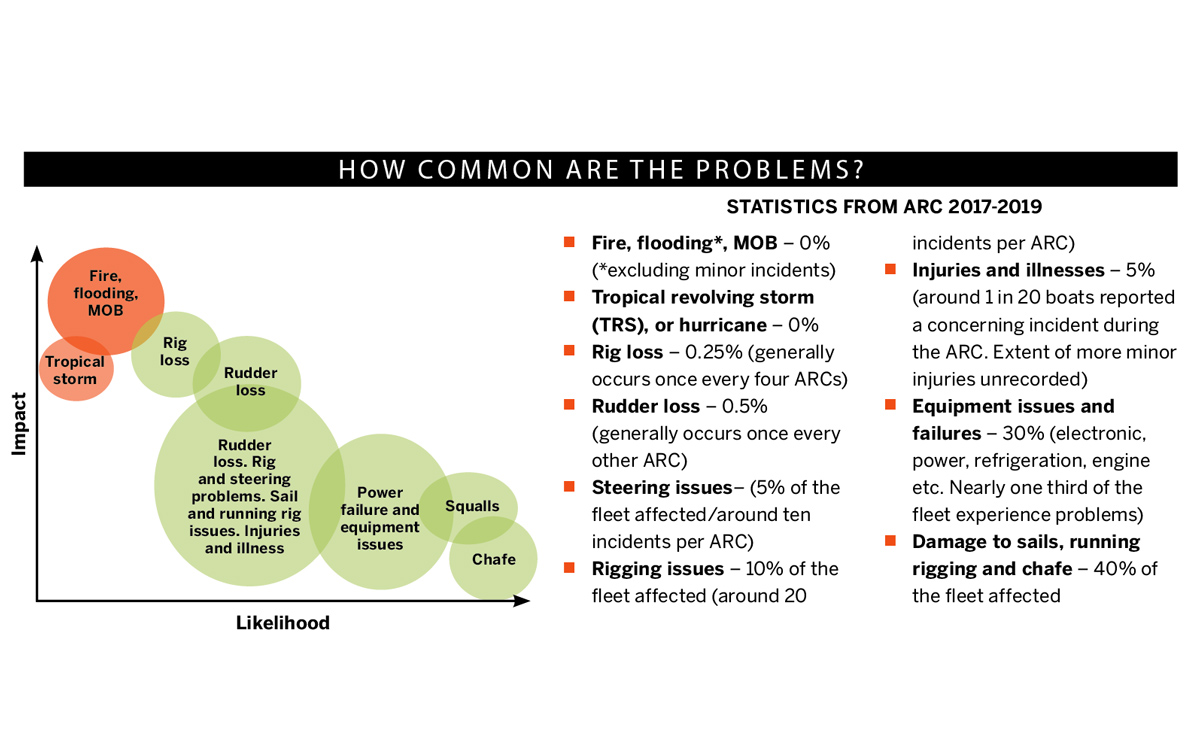

The trick with both planning for and dealing with problems at sea is to prioritise. Incidents such as fire, flooding and man overboard are fortunately rare if they have been considered. It is the problems more likely to occur that also need careful consideration.

An Oyster 575 sailing wing and wing. Note the port headsail sheet led back through a turning block at the boom end. Photo: TimBisMedia

Below are some of the problems well-prepared boats on a bluewater ocean crossing may encounter, based on incidents reported on the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) between 2017 and 2019. Rig, steering and equipment issues are among the most noteworthy.

Steering and rudder problems

These can be some of the most challenging issues and often happen without much warning. Downwind sailing in tradewinds can put huge strains on steering systems, especially during squalls or in acceleration zones, and particularly if a heavily laden yacht rounds up and broaches. The good news is that most of the potential problems can be prevented with checks, regular maintenance and a decent set of spares.

Choose wisely a system that will stand up to the miles, be easy to maintain, replace and check. I have appreciated yachts on which there was good access to steering systems and space to carry out repairs without dangling through a cockpit locker like a lemur.

Article continues below…

Atlantic sailing spares and repairs: Experienced skippers explain what you’ll need

You’ve got the plan, you’ve got the ideal offshore cruising yacht, you’ve got the time window – you’re set to…

Bluewater gear: Offshore cruising essentials and what they cost

What equipment do you need for bluewater voyaging and how should you prioritise your budget? This will always be a…

My ideal bluewater yacht would feature a system of solid rods linked through a gearbox although I have done most of my bluewater miles with the traditional cable and quadrant type systems. Sometimes it’s better the devil you know, so long as the system is robust.

A cable steering system spares list would include a big bag of bulldog clamps, spare cables and/or Spectra back-up, head torch and prop-up lamp, steering lubricants, double sets of spanners/sockets, and old toothbrushes for cleaning.

Consider whether your overall steering system has sufficient redundancy and how it interacts with your autopilots, which can operate off various parts of the system. A more costly but good arrangement for long-distance or round-the-world voyaging is to have two separate and switchable linear drive systems to the quadrant so that one can take over immediately if the other fails.

Typically, a handful of boats each year report steering problems during the ARC. This can be quite dramatic. Depending on your autopilot set-up and the failure, the autopilot may be able to keep control of the steering. If not, then you need to use an emergency tiller. While it can be used to steer the boat they’re only intended for short-term use to hold the rudder steady as you carry out repairs, sparing your fingers or worse.

On one occasion while using an emergency tiller to steer mid-ocean, the roll of the boat sent me flying, tiller in hand, across the back of the cockpit. I quickly secured a lanyard to the tiller and would encourage a crew to attach a lanyard in advance.

Emergency tiller hacks

This photo shows the manufacturer’s emergency tiller fitted on board a Hallberg-Rassy 64. It attaches to the stock under the bed in the aft cabin and is steered with the help of the rope purchase system. The purpose is to keep the rudder in a steady position while cables are replaced

Typical problems with emergency tillers: in the top photo the owner fitted davits, so the tiller cannot be turned to port. It also connects through a plate on deck, which allows excessive movement at the stock below

The solution: to shorten the tiller, add welded tangs for a purchase system, and a stainless steel plate with plastic bushing to fill the aperture where the tiller goes through on deck

A simple alternative using wood to fill the gap where the tiller meets the deck plate

A solution to stabilise an emergency tiller where the rudder stock is at cockpit level. A special tang is attached to an athwartships-secured spinnaker pole with Jubilee clips

The pole is then lashed to eyes welded on to the emergency tiller

Rudder damage

Collisions with underwater objects can cause serious rudder problems and are more common than being holed. Hitting sizeable flotsam and jetsam is the kind of thing that keeps sailors awake at night but it is actually a relatively rare occurrence — though on my last transatlantic, I encountered a floating fridge freezer.

Hitting marine mammals or sharks is more likely and there have been a couple of such incidents resulting in rudder damage this Atlantic season already. If ever there were a case for investing in a GoPro to take a look rather than donning the snorkel and mask, this is it! If a rudder does get damaged or lost, what are your options out on the ocean? A windvane self-steering system can double up as a spare rudder if you have one.

The easiest options are the drag methods of steering. These are going to get you back in control of the boat relatively quickly although with the penalty of reducing your speed. Streaming a drogue is ideal but even a coiled bunch of mooring warps can be effective.

A whale strike can cause significant damage

Set a drogue up with a bridle on to your cockpit winches to move the line from side to side. For narrower beam boats you can extend the bridle outboard using a spinnaker pole laid athwartships across the cockpit.

The enemy here is chafe so move the wear points and inspect the drag device regularly, putting in extra turns or chafe protection where needed. The drag methods may buy you time to have a go at attempting to jury-rig a rudder blade by affixing a board to a spinnaker pole or similar. In 2014 Ross Applebey did this on his Oyster Lightwave 48, Scarlet Oyster, during the Rolex Middle Sea race but only managed to get control of the yacht in relatively calm conditions.

A jammed rudder is often talked about as the most psychologically challenging problem. Add in the oceanic swell and a constantly circling boat and it’s no wonder it is sometimes the cause of crews abandoning an otherwise sound boat.

Balanced fin rudders rather than skeg-mounted rudders are more susceptible to impact damage, which can bend the stock or damage the bearings. Rudders can also jam up against the hull after a hard broach or impact and the steering stops or their mounting structure fails due to the high forces.

First, you must stop the boat circling; that will give everyone a huge boost. If you can get your boat to heave to, you should be able to balance the boat into submission. It may be necessary to use a drogue or the engine to help. With the boat stabilised you should be able to think more creatively to find a solution.

I have been towed a short distance with a jammed rudder and it was tricky but not impossible. One step to avoid this anguishing turn of events is to look carefully at both the stops and how they are mounted to the hull of the boat.

You may be able to use the emergency tiller or a lever attached to the rudder to winch the rudder free, if the stock is not badly bent. There have been occasions when crews have had to drop the rudder completely. This can be difficult but safely possible if rudder tube extends above the waterline.

![What equipment do you need for bluewater voyaging and how should you prioritise your budget? This will always be a prime consideration if you’re planning long-distance sailing, and to find the answers we sought the advice of the 258 skippers who took part in last year’s Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) rallies. We asked them what type of equipment they purchased for their voyages, how much it cost, and, having completed the ARC, which kit they rated most highly. We then followed up some of these skippers’ reports in more detail, taking a closer look at the equipment they chose and their budgets. In addition to skippers’ choice of bluewater gear, a large range of a safety kit is a non-negotiable element for all ARC sailors – indeed, for anyone heading offshore – so we examine the cost of safety gear and look at the training undertaken by skippers and crews before they set sail. Typical costs The average spend on equipment specifically for ocean cruising reported by last year’s ARC skippers was €32,398. That’s a surprisingly high figure, but it does need some further explanation. Six entrants spent over €100,000, which we assume includes major extras such as upgrades to mast, rig, and sails for newly purchased yachts, and this skewed the average somewhat. The highest concentration of spends were, however, between €10,000 and €30,000. More than half the skippers spent several tens of thousands of euros preparing their yachts for an Atlantic crossing and extended cruising, something confirmed in the case studies below. That isn’t to say that everyone thinking of going long-distance cruising has to spend such sums in one hit. We estimate that as many as 100 of the skippers surveyed already possessed the necessary bluewater equipment on their yachts, which were ready and fully equipped before their owners even signed up to the ARC. Recommended equipment Of the equipment the skippers did choose to spend extra money on, there were some notable recommendations: watermakers, solar panels, satellite communications, downwind sails such as a Parasailor and safety equipment (safety kit was the commonest area of spend). The responses and comments confirm that today’s cruisers want fresh water on tap rather than stowed in tanks or bottles, and power on demand – increasingly from sustainable rather than diesel-generated means. Sustainable power from hydrogenerators, wind turbines and solar panels, harnessed with large battery banks, is increasingly being chosen for distance cruising. Skippers are looking for a high level of safety equipment and they want to stay in touch, wherever they are. They also recognise the need for shade and the value of a good bimini. Cost to value ratio The most expensive piece of equipment bought, on average, was a diesel generator, but this was an upgrade chosen or required by only 23 skippers. Money spent on downwind sails, masts and rigging were the next highest amount – 26% of skippers bought new sails and 20% spent money upgrading mast and rigging. Watermakers are another costly upgrade at an average of €5,719 across 42 yachts, but a highly valued one, judging by most skippers’ feedback. We asked all ARC skippers to list their top five items of equipment bought specifically for the crossing, and watermakers were a clear favourite. The owner of Oyster 55 Princess Arguella said his Seafresh watermaker “really is top”, while the skipper of Hanse 531 Jack Rowland Smith went as far as to make his own prototype, stating it is: “less than half size of anything on the market and more efficient at 125lt/hr”. The greatest praise was reserved for Watt & Sea hydrogenerators, the Parasailor spinnaker and the Iridium GO! satellite wifi device. Dan Bower, the highly experienced skipper of Skye 51 Skyelark, reports: “Watt&Sea reduces reliance on generator/engine by up to three hours per day”. The crew of the Xc45 Nina of Southampton thinks it “a brilliant addition – little diesel generation needed”, praise that was seconded by the skipper of X-55 Makara of Exe. How gear performed The owner of Lagoon 450F SkyFall 1 describes a Parasailor as a ‘must have’ item after using it for what he estimated to be around 90% the crossing. Fellow Lagoon 450F owner agrees, adding that it is “perfect for downwind sailing” – and that comment was echoed by the skipper of Allures 39.9 Orion. Mark Thurlow, owner of Moody 49 Rum Truffle noted that a Parasailor provides “less rocking than other options and more control than a spinnaker.” Iridium GO! was carried by 95 yachts in the fleet as their primary means of satellite communication. The crew of Wight Spirit, a Contest 55, reports theirs was “very reliable for email and weather”. Princess Arguella thought it an “absolute lifeline as only means of communication”. The Norwegian skipper of the XC38 Malisa says he purchased the GO! after seeing a review in Yachting World and a recommendation by the ARC organisers and commented that it proved excellent. The owner of Beneteau 57 Mon Ami of Sweden commented that an AIS transponder (send and receive) is essential for a transatlantic crossing. The Canadian crew of Dobri Dani, an Elan Impression 434, highly rated their investment in new standing rigging as “insurance coverage and safety”. Also putting safety first was the skipper of Lagoon 400S2 La Boheme, describing his favourite investment, the Jordan series drogue, as a “panic button for extreme conditions”. One interesting aside is the top choice of the crew of Swan 68 Titania: a Sodastream machine, used to avoid the need for plastic bottles. Aventure’s owner praised a pressure cooker as a means of saving energy, something that Princess Arguella’s skipper also concurred with, adding that it helped them “dine like kings” aboard their Oyster 55. Safety gear In common with most other organised races and rallies, the ARC has compulsory safety requirements, and there are two ways of looking at the mandatory checklists and inspections. Some see it as an expensive obligation – the cost of the total safety kit list is at least £8,000 – while others look on it as a benchmark of best practice preparations. Interestingly, most of those who responded to our survey found the requirements a helpful way of preparing to a good standard. Roger Seymour is one of the ARC’s team of safety inspectors. He is a lifelong sailor with many ocean passages behind him and a Yachtmaster examiner. His job is to go through the equipment list in detail aboard each yacht to make sure it passes muster. “The most common problems we have are still with liferafts that are out of date and need servicing, or lifejackets, harnesses and liferings that are not suitable,” he says. “Sometimes people have bought lifejackets at the bottom end of the market so they aren’t fitted with a sprayhood or crotch straps and they will need to upgrade them. We require three-point harnesses and sometimes people resent that, but we are trying to do the best for them and their families. Liferings have to have the boat name on them, and have reflective tape, a light and whistle.” Seymour also cautions against relying on boatbuilders’ standard emergency arrangement for emergency steering or flooding, for example. “Boatbuilders are often looking at coastal sailing where there is close rescue and not the ultimate, so it’s a different approach,” says Seymour. “For example, people often have difficulty taking off inspection caps for the emergency tiller, and the rusty piece of metal that comes with the boat often doesn’t fit. If they have looked at it beforehand, they’ve normally resolved it. “Self sufficiency is what people need to think about. If your electrics fail or the water pump fails, can you get water out of the tanks? If the solenoid for the gas installation fails and it goes into the off position, can you bypass this?” Problems with batteries and sufficient energy are common. Perhaps these have not been replaced recently, and now crews are facing demands including lighting for nearly 12 hours of darkness each day. While an event checklist is “very reasonable” says Seymour, “If I was doing it, I would want to upgrade for flooding and fire. The list requires only two fire extinguishes, which is not enough in my view, and the number of bilge pumps are specified, but not the volume of water etc. That is something we discuss at seminars.” He finds that those who have been to an ISAF offshore sailing, first aid or sea survival courses, or ARC bluewater preparation weekend are “a thousand times better prepared because they have thought about all these scenarios. The difference is chalk and cheese.” But preparing for an ocean crossing is, he maintains, “nothing magic. Start early, talk to the crew, go over everything stem to stern and do a good shakedown cruise.” Safety training We asked some of the ARC crews what ocean-specific safety training they had undertaken, and whether they had found it useful. “We did a two-day course held by the Norwegian Rescue Association,” says Svein Lien. “I found it most useful as, in addition to theory, they had in-water practice with lifejackets and liferaft, and we tested [firing] flares. We said at least two people on board should have this training before the ARC, but three of the four crew we ended up with had actually done it. “I also found the safety guidance in the ARC handbook very good – and the inspection, though by that time we had it all sorted.” John Rutherford renewed his sea survival training before the ARC. “Essential”, he comments. “We didn’t need any of it but people need to know what to do in an emergency or a minor accident that could escalate very fast. It made us review what equipment we had on board. We were mostly OK but did add a drogue and double-checked the other equipment. I also did the medical officer course.” Australian skipper Emir Rudzic, sailing two-handed with his partner, Xin, had done a sea survival course “as part of my short racing career” and says he divided the preparations into three categories. “First, prevention. This is a no-expense-spared category, the one that is designed to prevent any emergency, and on top of this category was our forecasting subscription with PredictWind, their top plan, and an Iridium GO! with an unlimited data plan so we would have no barriers to checking the weather. “The other thing we included in this category was super comfortable lifejackets – top of the line Spinlocks – with three-point harnesses. Then we included radar, AIS, Forward Scan sonar and, cheapest of the safety equipment items we bought, a US$5 external buzzer that no one could sleep through. “The second category we put a reasonable emphasis on was tools. These were the type of things which would get you out of a pickle: bilge pump, fire blanket, MOB device, various spares, tools, power drill, etc. You can go nuts in this category but we got the basics plus a bit more. “The third category was emergency: liferaft, EPIRB, grab bag etc. But our idea was that if you plan the above two categories well you won’t ever need this one. And within this category we just needed to survive, and [we considered] it didn’t really matter if we were uncomfortable while surviving.” “You buy safety equipment in the hope it will never be needed,” John Rutherford says, “but having it gives peace of mind. It allows you to relax and not worry that minor problems will stop you from sailing. Although some of the equipment is expensive and will eventually be thrown away, don’t skimp.” Emir Rudzic strongly advises practising with safety equipment as part of your preparations. “What is important is to have a play with all your safety equipment. Open it, use it, put it together, practice with it, and do a test run. “When we got our Iridium we activated the SIM when we left Gibraltar and used Gibraltar to the Canary Islands as a test for the system. “Also it is important that everyone on board knows how to use all the equipment and knows where everything is, because we have our boat set up differently when doing long crossings compared with island-hopping.” Rudzic has posted a series of videos on his ARC preparations and experiences on the YouTube channel Sailing Hugo. Case study: Henrik Nyman Yacht: Pitanga (Oyster 745) Nationality: GBR Pitanga was already fully specced for offshore passagemaking before the ARC, but her owner says: “We bought a proper medical kit (£2,000), a Garmin inReach (£500), fishing equipment (£1,000), offshore sail repair kits (£2,000) and water filtering equipment (£100). We also got some extra spares for the engine, watermaker, etc, but [I consider them] a saving as they are expensive in the Caribbean, and we need them for normal maintenance.” Which gear represented the best value for money? “Without doubt the water filter. I like it so much that we use it full-time and the environment benefits make me feel good,” says Nyman. Equipment he rated highly (not least for the feelgood factor) was the fishing gear bought for the ARC. “We arrived in St Lucia with almost 25kg of fillets from various sorts of fishes in the freezer.” He’s not so sure about the medical kit. “It was very expensive and also needs a lot of [replacements] to be up to date. It also occupies a lot of space. We’ll likely downgrade to a coastal kit once we are back in the Med.” Besides the hardware needed, Nyman’s advice is to bring as much food as you can from the Canaries. “It is so expensive in Caribbean.” Case study: John Rutherford Yacht: Degree of Latitude (Oyster 45) Nationality: GBR Rutherford calculates that he spent over £46,000 on equipment and upgrades specifically for crossing the Atlantic with the rally. He bought a watermaker (£9,600), generator (£8,100), Fleet One satcom system (£4,800), twin headsails (£3,000) and upgraded in various areas. For example, he replaced the headsail furler (£4,600), the battery and power management system (£5,800), upgraded the autopilot drive (£3,400) and applied Coppercoat antifouling (£6,500). “There were also a host of small items and spares for everything in sight.” Not all turned out to be necessary, or even good value, however. The diesel generator was “not worth the money,” he believes. “A generator is needed but I believe a wind turbine would have fulfilled our needs with only a little engine time to boost it.” Nor was the watermaker essential. “It was useful but we could have carried enough water for the crossing,” he comments. Items that were worth spending on were the Fleet One satcoms – “necessary for the crossing, and worth every penny” – and the twin headsails – “best buy of all. We ran twin headsails for all but 36 hours of the crossing.” As for the upgrades and replacements, he says some “safety measures” that were made for the long crossing would have been necessary eventually. Case study: Emir Rudzic Yacht: Hugo EX (Oceanis 41.1) Nationality: AUS “I’m not sure we bought anything that was [solely] for the ARC,” says Rudzic. “Safety gear was probably the most costly, but since our boat was new we were spending that money anyway.” In total he reckons around €5,000 went on safety gear, but adds: “There were very few things on the ARC safety gear list we would not have bought anyway.” His best value items were a professional subscription to PredictWind and an Iridium GO! “which we consider the most important piece of safety gear we have onboard”. He also rated radar very highly: “Almost a must for a double-handed crew.” But there was nothing on the requirements list or installed for the crossing that he regretted buying and says: “If you use ARC’s safety gear list and preparation advice as a guide when you first get your boat, once it comes to preparing the boat you’ll spend very little extra money. There is nothing special about the ARC – everything the organisers recommend is stuff you should have.” Case study: Mark Thurlow Yacht: Rum Truffle (Moody 49) Nationality: GBR “We were pretty well set up for the ARC but in the spirit of your questions, here’s what we had for the transatlantic,” says Mark Thurlow. His extra items totalled over £18,000. • Hydrovane: £8,000 • Additional radar reflector: £300 • Additions to make our liferaft a 24-hour version: £250 • Additional electronic flares: £200 • Solar panels and arch: £2,000 • Parasailor: £8,000 To Thurlow’s mind, the best value items were the Hydrovane self-steering and solar panels. “Despite an issue with bolts, the Hydrovane was effective in steering without using power,” he comments. He was not so convinced of the necessity of the Parasailor, however. “It was great, but in strong winds with effectively a single crew on watch, wing on wing was an excellent and manageable downwind option,” he notes. His advice to others is to prepare early. “Preparing the boat over the previous two years, with the ARC manual as a reference, allowed us to buy additions at best prices and not have to rush purchases at the last minute. This, together with a comprehensive maintenance plan, kept issues with kit to the minimum. “I did fail to service the spinnaker pole, and this oversight did bite back with a breakage that I could not fix on passage,” he adds. “Carrying comprehensive spares and tools is essential.” Case study: Svein Lien Yacht: Fryd (Ovni 445) Nationality: NOR “We didn’t buy any equipment only for the ARC but the safety advice list helped us to equip the boat to a good standard,” says Lien. “Most of this would have come on board anyway.” Bluewater gear that he chose specifically for transoceanic sailing were a generator, watermaker, self-steering and a spinnaker, all of which he praises as “joyful equipment.” There was nothing he felt he could well have done without. Like others in the rally he victualled before leaving the Canaries. “The best advice I got was to stock up the boat with everything you possibly can find room for [in terms of] food, drinks and spares, as everything is much more expensive and difficult to get while in Caribbean.” Case study: Gorm Gondesen Yacht: Fica (Finot Conq FC53) Nationality: GER The best value items were the Schenker Smart 60 DC watermaker (approx £6,000) and the Watt&Sea 600 hydrogenerator (approx £5,000). The watermaker was reliable and always produced good drinking water. “The only thing we regretted was that we didn’t have a good bimini protecting the cockpit or a tent over the foredeck hatches so we could leave them open at night at anchor when it rained.” Case study: Neil Chapman Yacht: Supertaff (Van der Stadt Rebel 41) Nationality: GBR “I spent approximately £8,000. Event fees were £2,000 and new equipment such as satcoms with Iridium GO! and YB Tracker were £2,000. Upgrading the autopilot and various other components were another £2,000, and travel and logistics a further £2,000.”](https://keyassets.timeincuk.net/inspirewp/live/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2019/06/bluewater-gear-arc-survey-2018-tintomara-rm-1350.jpg)